Shasta's (Almost) All Ass

May 24-26, 2002

Climbers: Matthew Reagan, Paul Rozelle, and The Octopus.

This expedition is dedicated

to Simon Karecki (1972-2001)

There's something about big mountains that keep drawing you back.

After getting whipped during Shastarama

2001, we figured that we merely needed to come back during prime

climbing season to reap all the benefits of big vertical and deep

snow. Nearly three feet of fresh the week before guaranteed a weekend

free of dust and suncups (although increasing the avalanche danger),

and we seemed good to go. The weather service suggested problems, but

as the weekend approached the forecast became milder.

Well, we made a go of it!

Paul and I hit the

road early Friday morning, zooming up I-5 on a crystal clear morning.

Clearer than I'd seen the Valley in a long time, and clear enough that

our goal appeared soon after we'd left Sacramento (right). The photo

was taken from over 130 miles away, and has only minimal digital

enhancement. We made excellent time and anticipated excellent

weather. Of course, the first of a few logistical blunders was

noticed at a food stop in Redding--where's my clothing bag? Ugh.

Working a more-than-full-time job really puts a dent in planning and

preparation. I knew I'd forgotten something...

Paul and I hit the

road early Friday morning, zooming up I-5 on a crystal clear morning.

Clearer than I'd seen the Valley in a long time, and clear enough that

our goal appeared soon after we'd left Sacramento (right). The photo

was taken from over 130 miles away, and has only minimal digital

enhancement. We made excellent time and anticipated excellent

weather. Of course, the first of a few logistical blunders was

noticed at a food stop in Redding--where's my clothing bag? Ugh.

Working a more-than-full-time job really puts a dent in planning and

preparation. I knew I'd forgotten something...

A stop at the

famous Fifth Season solved my gear problems (and let me upgrade to a

much-needed all-white wardrobe). Using the south-side routes made the

approach to the trailhead quite easy, too--an 11-mile drive up the

paved Everett Highway to the already crowded Bunny Flat, rather than

90 minutes on remote logging roads. Packed, outfitted, and somewhat

overloaded, we hit the trail by mid-afternoon (left).

A stop at the

famous Fifth Season solved my gear problems (and let me upgrade to a

much-needed all-white wardrobe). Using the south-side routes made the

approach to the trailhead quite easy, too--an 11-mile drive up the

paved Everett Highway to the already crowded Bunny Flat, rather than

90 minutes on remote logging roads. Packed, outfitted, and somewhat

overloaded, we hit the trail by mid-afternoon (left).

The Bunny Flat

area was well-trampled by hordes of daytrippers and Avalanche

Gulch-bound climbers. We stumbled around in the postholes, ditches,

and craters, and eventually found a clean skin track heading straight

up into the woods. The weight of our packs was quite noticable by

now. We'd cut back on a lot of gear compared to last summer (shaving

six pounds of shelter weight alone), but the addition of ski gear to

climbing gear and the extra food required for a four-day expedition

weighed us down. About a mile in, the skin tracks narrowed to a

single path, and this path seemed to be slowly bearing right. A GPS

check confirmed a routefinding blunder--the skiers were heading up to

Powder Bowl, not to Horse Camp! The hiking route had taken a hard

left at the top of the trampled meadow, while we'd worked our way up

the wooded ridge that separates Avy Gulch from Old Ski Bowl. This

gave us the opportunity for some wandering in the snowy trees, but

soon after our discovery Paul began to experience the first of many

problems with his rented Randonee setup. Something right off the shop

bench shouldn't fall off during a kick turn, should it? Several

in-field adjustments later, we skied some heavy powder and traversed

across the open slopes of the lower Avy Gulch drainage toward Horse

Camp (right).

The Bunny Flat

area was well-trampled by hordes of daytrippers and Avalanche

Gulch-bound climbers. We stumbled around in the postholes, ditches,

and craters, and eventually found a clean skin track heading straight

up into the woods. The weight of our packs was quite noticable by

now. We'd cut back on a lot of gear compared to last summer (shaving

six pounds of shelter weight alone), but the addition of ski gear to

climbing gear and the extra food required for a four-day expedition

weighed us down. About a mile in, the skin tracks narrowed to a

single path, and this path seemed to be slowly bearing right. A GPS

check confirmed a routefinding blunder--the skiers were heading up to

Powder Bowl, not to Horse Camp! The hiking route had taken a hard

left at the top of the trampled meadow, while we'd worked our way up

the wooded ridge that separates Avy Gulch from Old Ski Bowl. This

gave us the opportunity for some wandering in the snowy trees, but

soon after our discovery Paul began to experience the first of many

problems with his rented Randonee setup. Something right off the shop

bench shouldn't fall off during a kick turn, should it? Several

in-field adjustments later, we skied some heavy powder and traversed

across the open slopes of the lower Avy Gulch drainage toward Horse

Camp (right).

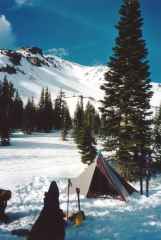

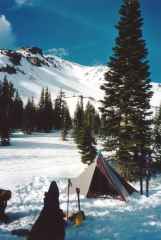

We still had hours of

sunlight to spare, though, and a full moon to look forward to after

sunset. The Megamid went up without excessive concern, and a very

comfortable camp was soon ready and fully Octopus-approved (left). We

went all-out, digging holes in the snow for comfortable sitting and

sculpting a proper kitchen area just outside the tent door. The 'Mid

is truly cavernous, with room for two people, two packs, and all the

wet and dirty gear one would normally have to stuff into a vestible.

Sure, we needed to carry 8 oz. tarps to keep our sleeping bags dry,

but the total weight still came in under 4.5 lbs. Not bad for 81

sq.ft. and room to sit up!

We still had hours of

sunlight to spare, though, and a full moon to look forward to after

sunset. The Megamid went up without excessive concern, and a very

comfortable camp was soon ready and fully Octopus-approved (left). We

went all-out, digging holes in the snow for comfortable sitting and

sculpting a proper kitchen area just outside the tent door. The 'Mid

is truly cavernous, with room for two people, two packs, and all the

wet and dirty gear one would normally have to stuff into a vestible.

Sure, we needed to carry 8 oz. tarps to keep our sleeping bags dry,

but the total weight still came in under 4.5 lbs. Not bad for 81

sq.ft. and room to sit up!

As we prepared

dinner, the setting sun illuminated the popular Avy Gulch climbing

route (right). The route is well-documented, and involves a stroll up

the Gulch toward Helen Lake on the highest of the visible moraines

(dead center in the photo, partly obscured by a curve in Casaval

Ridge) and then a climb to the right side of the Red Banks, the cliff

formation right of center. From there, you skirt the Konwakiton

Glacier headwall and bergshrund and "simply" walk up a long hill to

the summit. If the weather lets you, of course. We had more

ambitious plans. To avoid the crowds, our high camp would be in

Cascade Gulch, one drainage to the west, on a sheltered flat area

called Hidden Valley. This location would be less crowded, more

sanitary than Helen Lake, and would put us in the center of some of

the best backcountry skiing options in California. That was the

plan.

As we prepared

dinner, the setting sun illuminated the popular Avy Gulch climbing

route (right). The route is well-documented, and involves a stroll up

the Gulch toward Helen Lake on the highest of the visible moraines

(dead center in the photo, partly obscured by a curve in Casaval

Ridge) and then a climb to the right side of the Red Banks, the cliff

formation right of center. From there, you skirt the Konwakiton

Glacier headwall and bergshrund and "simply" walk up a long hill to

the summit. If the weather lets you, of course. We had more

ambitious plans. To avoid the crowds, our high camp would be in

Cascade Gulch, one drainage to the west, on a sheltered flat area

called Hidden Valley. This location would be less crowded, more

sanitary than Helen Lake, and would put us in the center of some of

the best backcountry skiing options in California. That was the

plan.

After dinner, we

checked the weather and climbing report down at the Sierra Club's

cabin (left), where rookie caretaker Ian told us what he knew about

routes, possible weekend weather, and potential crowd concerns.

Things didn't look great, sadly. The weather report that'd been

posted all week--storms on Saturday and Sunday--turned out to be true.

Perhaps the 'Mid would get a serious test after all? However, there

were several good ways to access Cascade Gulch, many of which involved

skiing some "bonus" terrain on the way in. Mmm.

After dinner, we

checked the weather and climbing report down at the Sierra Club's

cabin (left), where rookie caretaker Ian told us what he knew about

routes, possible weekend weather, and potential crowd concerns.

Things didn't look great, sadly. The weather report that'd been

posted all week--storms on Saturday and Sunday--turned out to be true.

Perhaps the 'Mid would get a serious test after all? However, there

were several good ways to access Cascade Gulch, many of which involved

skiing some "bonus" terrain on the way in. Mmm.

(Yeah, the baggy white Capilene ain't so stylish, but I was much

happier in full California sun than I would've been in my usually

all-black outfit)

The full moon, by the way, exceeded all expectations. Rarely does one

get to take a hike to 8,000' on a big mountain, with no wind, clear

skies, and enough moonlight to make headlamps completely unnecessary.

Out on the slopes of the Gulch, well above treeline, we pulled out the

last of the Expedition Scotch and toasted our friend who couldn't be

with us.

Saturday dawned clear and calm, despite the threats of bad weather. I

hadn't slept much that night due to a combination of altitude and a

horde of hungry mice that ran in circles around the inside of the tent

and crunched away at our food supply (I never thought of hanging food

in the winter!). Chocolate-covered raisins were a bigger hit than

peanuts. They didn't get into the caffiene supply, though, and I

managed to chase away the one that was trying to chew into my

Gatorade-filled Platypus. Thanks to our big packs, we didn't want for

food despite the intrusion.

Breaking camp

around 8am, we hoisted our (still heavy) packs and followed a GPS

bearing up and around the lower reaches of Casaval Ridge toward our

high camp in Hidden Valley. The exact route wasn't entirely clear. A

few ski tracks headed down and to the west, a bunch of skin tracks

headed up the ridge to popular ski runs (Giddy-Giddy and the "windows"

in Casaval Ridge), and a snowshoe track cut a rising traverse that

best approximated the standard climbing route. This was a steep climb

that required many switchbacks (right), both due to the nature of the

terrain and due to the fact that Paul's AT kept coming apart. The

adjustments made in camp the night before wouldn't hold, and the

toepiece simply refused to deal with the forces generated by 210lbs of

skier and pack stomping a steep track up refrozen snow.

Breaking camp

around 8am, we hoisted our (still heavy) packs and followed a GPS

bearing up and around the lower reaches of Casaval Ridge toward our

high camp in Hidden Valley. The exact route wasn't entirely clear. A

few ski tracks headed down and to the west, a bunch of skin tracks

headed up the ridge to popular ski runs (Giddy-Giddy and the "windows"

in Casaval Ridge), and a snowshoe track cut a rising traverse that

best approximated the standard climbing route. This was a steep climb

that required many switchbacks (right), both due to the nature of the

terrain and due to the fact that Paul's AT kept coming apart. The

adjustments made in camp the night before wouldn't hold, and the

toepiece simply refused to deal with the forces generated by 210lbs of

skier and pack stomping a steep track up refrozen snow.

Then, as the sun warmed the snow, the skin problems began. I'd

recently purchased a set of full-width Ascensions for my new telemark

gear, and so I had fresh glue, edge-to-edge coverage, and the kind of

climbing security that is the signature of "Climbing Purple Vertical

Eaters." Paul's 55mm Euro-tip skins were light on glue, stretched

when wet, balled up tons of snow, and wouldn't bite in a steep, firm

skin track. Anyone who's struggled with substandard skins knows the

frustration of sudden releases, sideways sliding, and frequent falls.

Add an expedition pack and difficult terrain to create the perfect

skiing nightmare.

We inched up the broad gully (perfect for skiing, although that wasn't

on our minds at the moment) as the hours passed and the heat of the

day kicked in. It was only a few miles and 1,500' from Horse Camp to

the col above Hidden Valley, but heavy packs and frequent equipment

failures made the going slow. It was too steep for an uphill track,

and the AT gear wasn't going to hold together on long traverses.

Eventually, Paul simply gave up, hoisted the skis onto the already

overloaded pack, and started hoofing it.

By mid-afternoon we

reached our goal, the col at 9,400' that provides a high entrance to

Hidden Valley (left). Despite somewhat icy conditions, I had enough

skin grip to chug straight up to the col while Paul took a safer route

high to the right. As I shuffled up the last few vertical feet, a

tremendous vista was revealed, encompassing Shastina, the Cascade

Gulch valley, the vast West Face of Shasta, and the sheltered and

spacious flats of Hidden Valley at the base of numerous skiable runs.

As promised by Ian, I was standing at the top of one such run--a wide

bowl offering 300-400' of perfect, smooth corn that ran out right by

our desired campsite. I was also standing five feet short of a

huge cornice. Uh oh, so that's why the horizon line was so

sharp. A look to the left showed me where the Cornice connected

directly to the sheer rock wall that formed the south side of the

Valley. A look to the right revealed steeper slopes and an opening in

the cornice--that dumped into a 10' wide, 45-50 degree rock-lined

chute. Hmm. That would be hard enough without the 50lb pack.

Perhaps the rope would've been a useful addition to the luggage? I

was so dejected I forget to snap any pictures of the magnificent

panorama.

By mid-afternoon we

reached our goal, the col at 9,400' that provides a high entrance to

Hidden Valley (left). Despite somewhat icy conditions, I had enough

skin grip to chug straight up to the col while Paul took a safer route

high to the right. As I shuffled up the last few vertical feet, a

tremendous vista was revealed, encompassing Shastina, the Cascade

Gulch valley, the vast West Face of Shasta, and the sheltered and

spacious flats of Hidden Valley at the base of numerous skiable runs.

As promised by Ian, I was standing at the top of one such run--a wide

bowl offering 300-400' of perfect, smooth corn that ran out right by

our desired campsite. I was also standing five feet short of a

huge cornice. Uh oh, so that's why the horizon line was so

sharp. A look to the left showed me where the Cornice connected

directly to the sheer rock wall that formed the south side of the

Valley. A look to the right revealed steeper slopes and an opening in

the cornice--that dumped into a 10' wide, 45-50 degree rock-lined

chute. Hmm. That would be hard enough without the 50lb pack.

Perhaps the rope would've been a useful addition to the luggage? I

was so dejected I forget to snap any pictures of the magnificent

panorama.

(Looking at our GPS track on the map, I still can't fully

reconcile this experience with the map. Wind loading must've sculpted

that 200' slope, less steep on the topo than what we'd just climbed,

into a frozen wave. Inching towards the lip and peering sideways, the

landing zone seemed a dozen feet or more below the lip. I guess we

should've brought a rope and anchors for just this sort of occasion.

Ah, but there's the weight question once again!)

I shuffled back to the top of the broad couloir, meeting Paul just as

he made it to the top, and broke the bad news. Yep, the reports of

"wind loading from all directions" were true, and our ambition had

kicked our sorry asses. Paul skied down and to the west a bit,

checking out the scrubby traverse we'd seen other climbers take (this

is the exact climbing route listed on the map), but it was steep and

too scrubby to be ski-friendly. While Paul searched, I de-skinned and

clicked my Hammerheads into a stiffer setting. Something was

bothering me, but I didn't know what it was. I started down first,

cutting a wide traverse across the steep but perfectly-smooth slope

while I figured out how to tele with all this weight on my back. As I

turned around to watch Paul, I remembered one other thing about the

view of Shastina--it had a black background! The ridge we'd been

skiing down now had a black background as well, and a rumble of

thunder brought me back to my senses. Time to ski!

And fine skiing it

was, despite Paul's cranky and unreliable AT gear and our heavy packs.

The gully delivered a steep face, a gentle narrows, and another steep

face. Lower down, various detours into the scrub presented themselves

and allowed for creative routefinding (right). All of this was coated

in a smooth layer of slush atop a solid base. Slushy enough to throw

a few pinwheels, but not yet deep enough to slough. A few drops of

rain, however, indicated that things would soon be softening up quite

a bit in the near future.

And fine skiing it

was, despite Paul's cranky and unreliable AT gear and our heavy packs.

The gully delivered a steep face, a gentle narrows, and another steep

face. Lower down, various detours into the scrub presented themselves

and allowed for creative routefinding (right). All of this was coated

in a smooth layer of slush atop a solid base. Slushy enough to throw

a few pinwheels, but not yet deep enough to slough. A few drops of

rain, however, indicated that things would soon be softening up quite

a bit in the near future.

We kept an eye on the GPS, stopping at the waypoint we'd set as we

left our woods traverse. Here, we decided to go a little lower to

avoid the rolling traverses that sucked up so much energy that

morning. The lower, steeper face had fewer trees, though, and

therefore more sun exposure and less snow.  Paul, still,

accustomed to New England bushwacking ways (and skiing rented gear)

didn't see a problem with this (left). Knowing how nasty volcanic

rocks can be to new, lightweight tele skis, I found a less direct but

better-covered path through the shrubbery. We found the lower

traverse and followed the old ski tracks across the Casaval gullies

and back to Horse Camp, where we claimed our old campsite.

Paul, still,

accustomed to New England bushwacking ways (and skiing rented gear)

didn't see a problem with this (left). Knowing how nasty volcanic

rocks can be to new, lightweight tele skis, I found a less direct but

better-covered path through the shrubbery. We found the lower

traverse and followed the old ski tracks across the Casaval gullies

and back to Horse Camp, where we claimed our old campsite.

We made it just in time, too, as the rain and hail from the

approaching storm caught us just after we'd reraised the Megamid. To

keep things dry in a floorless tent, we dug out 12-18" trenches around

our snow platform, with channels to drain water into a natural sump

(treewell) just above our campsite. We tossed our gear inside and

retreated to the Horse Camp cabin to wait out the storm. Several

storms passed through over the next few hours, dumping sleet, hail,

and plenty of rain on the still unconsolidated snow from the week

before. Wet and dejected climbers streamed down from aborted attempts

to reach Helen Lake. We set a reasonable turn-around criterium--we'll

stay if the weather clears in time for dinner. Luckily, it

did.

That night, we

slept better despite occasional incursions by more rogue rodents (I

had no food in my pack, but apparantly chewing on my pack towel was

interesting enough for the critters). It stayed warm and damp most of

the night, but strong downslope winds appeared around 3am and by

sunrise the temperatures had dropped a bit below freezing. All the

folks we'd heard heading up at midnight, 1am, and 3am could be seen

climbing up below the Red Banks, with thick fog shrouding the top of

the couloir. As the sun rose and the clouds thinned, a lenticular

cloud could be see over the top of Sargents Ridge (right). Not a good

day for climbing, it seems.

That night, we

slept better despite occasional incursions by more rogue rodents (I

had no food in my pack, but apparantly chewing on my pack towel was

interesting enough for the critters). It stayed warm and damp most of

the night, but strong downslope winds appeared around 3am and by

sunrise the temperatures had dropped a bit below freezing. All the

folks we'd heard heading up at midnight, 1am, and 3am could be seen

climbing up below the Red Banks, with thick fog shrouding the top of

the couloir. As the sun rose and the clouds thinned, a lenticular

cloud could be see over the top of Sargents Ridge (right). Not a good

day for climbing, it seems.

But there are better

things to do on a mountain. We took a leisurely breakfast, enjoying

our luxurious campsite and working our way through the extra food.

Slowly, the sun appeared and started to work on the crusty snow. We

sorted gear, packed gear, got more weather info from Ian (heavy

thunderstorms in the afternoon/evening), and hoisted lightweight

daypacks for some serious skiing (left).

But there are better

things to do on a mountain. We took a leisurely breakfast, enjoying

our luxurious campsite and working our way through the extra food.

Slowly, the sun appeared and started to work on the crusty snow. We

sorted gear, packed gear, got more weather info from Ian (heavy

thunderstorms in the afternoon/evening), and hoisted lightweight

daypacks for some serious skiing (left).

We quickly skinned a thousand feet above Horse Camp and searched for

East-facing aspects that would be soaking up the morning sun.

Compared to our struggles the day before, we easily devoured the

vertical and ended up waiting around for the sun to catch up with us.

We started with some warm-up turns on a short slope below Casaval

Ridge, and soon worked up to some leisurely cruising through smooth

corn (right).  By now, the sun was

out, the sky was blue, and the heat was building, so we found a more

aggressive track and sought out bigger, steeper, and longer runs. Two

jaunts up the Avy Gulch climbers path brought us to the level slopes

of 50/50 flat around 9,700', giving us two awesome 1,000' cruises down

the morainal hills.

By now, the sun was

out, the sky was blue, and the heat was building, so we found a more

aggressive track and sought out bigger, steeper, and longer runs. Two

jaunts up the Avy Gulch climbers path brought us to the level slopes

of 50/50 flat around 9,700', giving us two awesome 1,000' cruises down

the morainal hills.

It was so good, the

Telepus made an appearance (left).

It was so good, the

Telepus made an appearance (left).

But backcountry

skiing is a morning activity, and soon after lunchtime the clouds

started to build once again (right). We stayed to skiers right all

the way down the Gulch, carving through corn, slush, slop, and the

postholed climbers' track on the way back to the campsite.

But backcountry

skiing is a morning activity, and soon after lunchtime the clouds

started to build once again (right). We stayed to skiers right all

the way down the Gulch, carving through corn, slush, slop, and the

postholed climbers' track on the way back to the campsite.

We broke camp,

shouldered those heavy packs (a bit lighter due to food donations),

and skied the well-beated path back to Bunny Flat. The famous Shasta

Lemurians sent out an escort of UFOs to say goodbye (left). We still

had one day left, and after a good night's sleep in Livermore, we

headed out for more skiing at Tioga Pass.

We broke camp,

shouldered those heavy packs (a bit lighter due to food donations),

and skied the well-beated path back to Bunny Flat. The famous Shasta

Lemurians sent out an escort of UFOs to say goodbye (left). We still

had one day left, and after a good night's sleep in Livermore, we

headed out for more skiing at Tioga Pass.

Expedition Map

So what did we learn on this trip?

- Climb or ski? To do both requires a lot of gear. We went

"lighter" this time, but made up for that saved weight by hauling the

ski equipment. A six-pound rope could've solved the cornice problem,

but that would have been more weight. A longer trip with a

permanent base seems to be one way to deal with multiple sets of toys,

with skiing day trips and a separate climbing expedition (with or

without a high camp). If we'd taken the detour to Hidden Valley, we

would have arrived at the "end" of the ski day, would've had Sunday as

a climbing day, and only Monday would have allowed for serious ski

time, most of it with a full pack. So much terrain, so little time!

The other option is to be realistic about what one is trying to

accomplish. The fact that we climbed twice the vertical in half the

time on Sunday compared to Saturday shows that the "standard" rules

for computing time-distance-altitude don't properly account for pack

weight. Then, there's #2.

- Invest in the best gear. Rentals suck. We probably wasted at

least an hour on Saturday due to skin/binding problems. The

psychological toll of cranky gear is much harder to deal with than the

physical toll of a ski haul. You want wide skins, fresh skin glue,

well-fitted boots, and bindings you trust. Or, you want quality

lightweight gear that gives you freedom and speed. Yeah it costs

money, but so does getting up to the mountains (especially for those

who travel). Pay now or pay later.

- Look into special ski routes. Ritchin's ski route, a lower

traverse into Cascade Gulch, would have involved much longer stretches

of steep skinning (see #2), but we wouldn't have had to deal with a

cornice and climber-style routefinding. We probably could have made

it around the west side of the gully (the standard climbing route)

with only moderate frustration, but then again, we were probably an

hour too late to get the camp set up in time to avoid the

thunderstorms.

- AT gear doesn't seem as comfortable on more rolling and variable

terrain, so this should be part of route selection (or gear selection,

perhaps). A Hammerhead in

position #1 skis pretty well, while an AT binding needs to be locked

down.

- Create new rice-based meals. The best food we ate was the

lightest and simplest. There's better powdered bullion out there than

the cubes of salt and yellow food coloring, so use it! Perhaps I

should look into a food dehydrator...

I hope I get a chance to test these hypotheses in June with an

east-side ski expedition!

photos by Matthew Reagan and Paul Rozelle

Back to Outdoor Adventures

Paul and I hit the

road early Friday morning, zooming up I-5 on a crystal clear morning.

Clearer than I'd seen the Valley in a long time, and clear enough that

our goal appeared soon after we'd left Sacramento (right). The photo

was taken from over 130 miles away, and has only minimal digital

enhancement. We made excellent time and anticipated excellent

weather. Of course, the first of a few logistical blunders was

noticed at a food stop in Redding--where's my clothing bag? Ugh.

Working a more-than-full-time job really puts a dent in planning and

preparation. I knew I'd forgotten something...

Paul and I hit the

road early Friday morning, zooming up I-5 on a crystal clear morning.

Clearer than I'd seen the Valley in a long time, and clear enough that

our goal appeared soon after we'd left Sacramento (right). The photo

was taken from over 130 miles away, and has only minimal digital

enhancement. We made excellent time and anticipated excellent

weather. Of course, the first of a few logistical blunders was

noticed at a food stop in Redding--where's my clothing bag? Ugh.

Working a more-than-full-time job really puts a dent in planning and

preparation. I knew I'd forgotten something...